WHAT

In 2014, the Government invited oil and gas companies to bid for exclusive rights/ licences to explore and potentially develop oil and gas in about 40% of Britain, in the 14th round for onshore licences.

In August 2015, the Government revealed it was considering offering up the coastal area of Somerset to the successful bidder.

In December 2015, it confirmed South Western Energy – a company based in South Wales – was the successful applicant.

In September 2016 Petroleum Exploration and Development Licences (PEDLs) came into effect in North and West Somerset after SW Energy officially accepted the licences. They turned down others they were offered for Wiltshire and the Forest of Dean, citing lack of finance (and one of the directors also admitted the massive level of public opposition was another reason). SW Energy also accepted PEDLs in Dorset.

The PEDLs (licences) are effectively a contract between the Government and South Western Energy, and have been granted on the condition that SW Energy drills at least two exploratory wells to a depth of more than 1000m. The PEDLs allow until July 2021 to do this, but as can be seen with the previous round licences across Britain, can often be granted extensions if the company fails to complete their agreed ‘work programme’ on time.

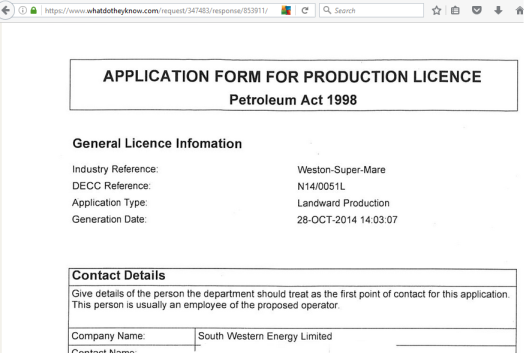

In its licence application (obtained via a Freedom of Information request) and actual licences (PEDL320, PEDL321 and PEDL344 published on the Oil & Gas Authority website), SW Energy revealed its main interest is in Lower Carboniferous Shales – this would ultimately mean fracking to get the gas out following exploratory work – with a secondary interest in Devonian and Silurian rock layers, which could mean fracking or ‘conventional’ gas or oil recovery.

Conventional oil and gas involves a vertical well tapping into an underground reservoir, and the oil or gas flowing out without the need to cause fractures in rocks (ie the traditional way of getting oil and gas). Nowadays, conventional wells can be extended to become fracking wells, so conventional oil and gas – while seeming more benign – have become gateways for fracking (see Kirby Misperton in Ryedale, North Yorkshire).

Fracking – or high-volume slickwater hydraulic fracturing to give it its full title – is when a mix of water, silica sand and chemicals is blasted at exceedingly high pressure up to 5 miles down a diagonal or horizontal hole to cause shale rocks to explode in order to recover natural gas/ methane (or oil). The main risks are water contamination, earthquakes and subsidence, health impacts including respiratory, problems with fertility and cancers, destruction of the natural environment, that hundreds of wells will be required within a licence area over 20 years of production to make it economically viable, and also infrastructure incapable of dealing with extra traffic, water and sand resources, and treatment facilities for radioactive and toxic wastewater.

When/if South Western Energy gets to the stage of its initial applications the company will almost certainly insist it is not going to frack – but only drill a vertical well to sample rock cores and take them to a laboratory to test their potential for oil and gas.

Councillors faced with applications, will likely be compelled by planning law to not consider that these exploratory wells are a gateway for fracking – they will also not be allowed to consider the 800+ peer-reviewed scientific studies showing harm caused by fracking as they relate to the US and not “gold standard regulated” Britain, nor will they be permitted to consider that public opinion nationally and locally is overwhelmingly against fracking.

If SW Energy is able to claim that there is shale gas available from its exploratory wells then it will either try and sell on licences to established fracking firms such as Igas, Cuadrilla or INEOS or raise the finances itself to develop Somerset into a fracking zone for another 20 years.

The Infrastructure Act 2015 permits “any substance” (eg fracking chemicals, waste) to be left in the ground, for any gas or oil discovered anywhere to be recovered as a “legal objective”, and allows a Government minister to overrule any local democratic decision. This year we have seen the minister overrule the decision to turn down two fracking operations in Lancashire, and councils in North Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire approve fracking, despite more than 99% of respondents in each case objecting and in the Notts case, the site being located on a site littered with unexploded bombs and very close to a nature reserve.

So what the people of Somerset need to do is to make sure fracking does not get to the application stage – because then it is much harder to fight. Every section of the Somerset community – people of all classes, political persuasions, subcultures, occupations and age groups – need to help the national effort to get fracking banned in England (it is currently suspended in Wales and Scotland), to show there is no social licence for fracking/ gas exploration and prevent it from getting a toehold.

The time to get started is now, not later! And resistance is starting so if you’re in Somerset, get involved… If it’s not nipped in the bud, the fracking industry will have to be stopped by mass direct action.

WHERE

It’s important to remember that wherever the drill sites will be located, a radius of 10km around them will be the Government-proscribed “zone of influence” – there could eventually be 20 wells per site, all drilling directionally (diagonally) or vertically and then horizontally for miles in any direction.

Ostensibly fracking would need to take place at least 1000m below ground (and 1200m below ground in “protected areas” – no one has explained why 200m extra depth makes all the difference) BUT as fracking is only legally defined as using a certain amount of fluid (more than 1,000 cubic metres per frack, and 10,000 per operation), potentially frackers could get around the restrictions if they could manage with less fluid.

When South Western Energy made its initial application in October 2014, it referred to seven 10x10km Ordnance Survey grid blocks (which now comprise three licences) as “Weston-super-Mare” and proposed to drill down a minimum of 300 metres. This was before the 1000/1200m restrictions came into being.

It’s likely that closest to Weston, geologically the drillers would encounter their stated principle target rock layer, the Avon Group aka the Lower Carboniferous Limestone Shale, at such a shallow depth – further south towards Bridgwater, the layer dips down considerably – while it seems (according to the British Geological Survey – see the map below showing the extent of Carboniferous Limestone) it would be non-existent at any depth west of the River Parrett.

But as wells can be drilled directionally as well as straight down (vertically) none of the below areas can be ruled out.

The most major factor for a well site is unlikely to be an environmental or even a geological consideration – it will be wherever South Western Energy can persuade a landowner to agree access.

And they have 342 square km in which to explore.

Theoretically the licence allows drilling to take place anywhere, even in “protected zones” (these include 1km buffer zones around designated nature and conservation sites – some protected by the EU, so liable to be not protected following Brexit)… but fracking is not allowed, so it would not be cost-effective for wells to be drilled if they could not be extended and converted into fracking. However, laws can be made more lax and loopholes can be exploited, so NOWHERE within the licencing area can really be ruled out. (Indeed, a search of other licences reveals that in one case, in Hampshire, a drill site is actually several hundred metres outside a PEDL area!)

Here closest below are my own roughly-drawn interpretations on clearer Google mapping from poor-quality maps on the licences (PEDLs) themselves… I may be a researcher, but as you can see I’m no graphics ace! You can check the originals yourselves from the licences (see further below). The areas inside the red lines are where drill sites could potentially be situated.

So

So within the LIKELY zones for well sites are…

PEDL 344 –

Dunster (east of)

Carhampton

Withycombe

Blue Anchor

Old Cleeve

Washford

Watchet

Doniford

Williton

Weacombe

Staple

West Quantoxhead

East Quantoxhead

Kilve

Lilstock

Stringston

Stogursey

Fiddington

Combwich

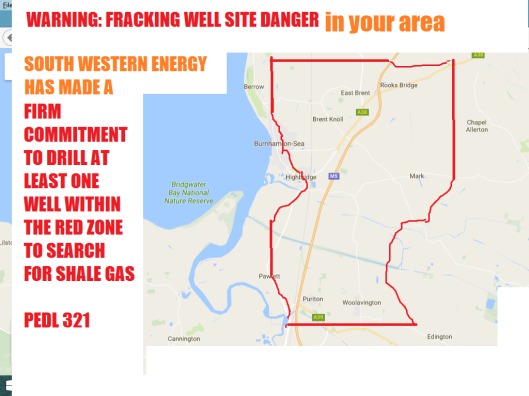

PEDL 321 –

Rooks Bridge

East Brent

Brent Knoll

Mark

Burnham-on-Sea (east)

Highbridge

Pawlett

Puriton

Woolavington

PEDL 320 –

Kenn

St Georges

Kewstoke

Weston-super-Mare (eastern side)

Locking

Banwell (northern side)

Hutton

Bleadon

Anywhere situated within 10km of these places could be drilled under, have a cocktail of chemicals, water and frack sand blasted at high pressure, causing the rocks to crack. This includes Hinkley nuclear power stations!

Here’s a bit more detail from the licences – you could say PEDL320 is centred on Weston, PEDL321 on Burnham, and PEDL344 on Watchet. Note that the outer ring is the “zone of influence”, so fracking could take place anywhere underground within this bubble.

(I’ll attempt to explain the Silurian issue further down… as for the expression Drill or Drop, it means the company is obliged to investigate drilling but can decide not to if its preliminary investigations reveal finding gas/oil is not feasible)

(most of Weston-super-Mare is unprotected from fracking)

(all of ST25a is within a protected area, so no actual high-volume slickwater hydraulic fracturing that uses more than 1,000 cubic metres of fluid per frack not allowed, everything else seems ok!)

(the Government has granted the licence PEDL321 on condition the company drills one well to 1500m depth within this licensed area)

[Bridgwater, Street and some of Glastonbury within the zone of influence… only some of the Levels are “protected”]

[a deeper commitment here, possible reasons explained later – also note interest in the Devonian rocks]

[Hinkley Point nuclear power stations are within the block in the (inadequately) “protected” Severn Estuary area]

[no protection for the coastline]

[Butlins and Minehead could be fracked under, as could the Brendon and Quantock Hills]

WHO

This is Gerwyn Llewellyn Williams, the so-called (by The Sun) Prince of Shales – he is owner, director and financier (it appears) of South Western Energy and about 20 other companies, most with his wife Shelagh Rose as co-director and Cardiff-based geologist Oliver Taylor.

I have met Gerwyn and Oliver – pleasant enough people, were it not for their intentions! However, at our meeting they denied wanting to look for shale gas in the Forest of Dean (which we later discovered was a fib, as their licence application and unissued licences showed they were intending to), so we wouldn’t advise people give much credence to any utterances from the pair.

I have also done extensive research into Gerwyn’s/SW Energy’s apparent financial capability. If you have time, read my five-part blog on the subject (needs updating, as now the company has withdrawn from Wilts and the Forest of Dean, and has relinquished some of his licences under the names of UK Onshore Gas/ UK Methane/ Coastal Gas in South Wales, and held on to others.

Some in Somerset may recall meeting Gerwyn and Oliver in the past – in 2011 their company UK Methane to drill for coalbed methane in the Keynsham area: See Marco Jackson’s excellent film for Frack Free Somerset, The Truth Behind The Dash For Gas (2014) (watch here on YouTube, better still arrange a public viewing) for more information. Bath & North East Somerset Council’s request for information proved too much for the company, and UK Methane withdrew its applications and eventually relinquished its licences.

However, since then the Infrastructure Act 2015 has come into being, which makes it much harder for councils to refuse planning permission for fracking.

He passed the Government financial competence test (the Government won’t release that information), but if he has any money it can’t be found on public record – although the Jersey-based Damor Investors (linked to the Royal Bank of Canada and the Panama Papers) and his own vehicle, Luxembourg-based Infinity Energy are in the mix.

He and Oliver have been involved in coalbed methane and abandoned mine methane production, but there is no sign they have ever developed shale gas – although Gerwyn has expressed a wish to, in South Wales where he claims there is more shale gas available than in Lancashire! Strangely, the Australian partner Eden Energy (or Adamo as its UK branch is called) didn’t seem to agree, and ended up giving all its shares and the company Adamo in the South Wales venture to Gerwyn and Oliver for £1. Gerwyn currently has planning permission to explore for coalbed methane and shale gas in several locations in South Wales. As there is a moratorium on fracking in Wales, he can’t go into development and fracking, as much as he wants to.

A South Wales blogger has described Gerwyn’s activities as a Ponzi scheme to get a quick buck for his retirement, and to complete his massive monstrosity of a concrete palace on the Welsh riviera, near Porthcawl.

HOW

Oliver from South Western Energy is initially “building a geological model”. This is by inputting data into mapping software used by oil and gas prospectors. They don’t appear to have much data to input. There has only been one gas/oil venture in the area, conventional oil production in Kilve, in the Quantocks, during the 1920s. This was in the Jurassic rock layer which lies a long way above SW Energy’s target rocks. There was a borehole drilled in Weston-super-Mare in 1911 which shows carboniferous limestone layers began at 828ft (252m), it appears the only other deep borehole (marked on the map below with a blue dot) drilled in 1971 at Burton Row, near Brent Knoll, went down more than 1100m and reached what was believed to be (but not certain) Permian rock, which is one era more recent than carboniferous, therefore any carboniferous limestone would be somewhere below this, and Devonian and Silurian rock much further again below.

There has been just one 2D seismic survey to the east of the PEDL areas which will provide limited information. It should be noted that the reason why there were two earthquakes in Lancashire in 2011, attributed to the first-ever onshore UK fracking attempt, was attributed to Cuadrilla drilling into a fault because its 2D seismic data was inaccurate. Obtaining seismic data is an invasive process – it either involves the shallow burial of explosives, or “thumper” trucks – in order to record imagery or data by stimulating earth tremors.

According to the licences’ work programmes, South Western Energy is not expected to obtain – or “shoot” – any 2D or 3D seismic data.

[the bottom group of three grey squares show the three Somerset licence areas, the blue dot a deep borehole drilled to look at rock strata in the 1971, the green line to the right of the blocks shows the location of a 2D seismic survey, and the various colours show the different rock types that outcrop (are at or close to the surface) – the turquoise represents five or more carboniferous limestone series, and the lowest/oldest of these layers is the main object of the frackers – this limestone continues below younger rock layers and the Severn Estuary/ Bristol Channel, notably the grey which represents jurassic and pink triassic, but only as far west as Bridgwater/ River Parrett… below everything on this map, at up to five miles beneath ground, are various Devonian and Silurian layers marked mostly in orange/red, purples and mauves… the darker pink in the Quantocks/ North Devon area is Middle Devonian]

However, this is a much-faulted part of the world, as this geological map shows:

In PEDL344 (Watchet area), South Western Energy have committed to drilling to a depth of 1,800m to reach the Avon Group (aka Lower Limestone Shales), Devonian and Silurian levels. This is questionable geologically. It would appear (though not proven) that they will not encounter the Avon Group at all west of Bridgwater, they may reach the Devonian level if they drill inland, but the Silurian is likely to be a mile or so further underground.

South Western Energy told us they weren’t interested in Silurian rocks – they are such a long way down it would be much more expensive to look, and exploration in Poland and also deep boreholes and seismic profiling in South-East Wales and Herefordshire indicate the rocks are too old and too far down to still contain oil or gas.

Once South Western Energy have managed to secure a site(s) by means of an access agreement with a landowner, they will need to raise the money to drill an exploratory well. The Government’s inconsistent redactions of “commercially sensitive information” means we can’t see the cost estimates for Somerset, but as a guideline the non-redacted information from the Forest of Dean (for one “firm commitment” PEDL and one “drill or drop”) shows:

Before they start drilling, SW Energy must follow a ‘regulatory roadmap’ and obtain a number of consents. It should be said though that the Environment Agency and other agencies have so far been almost totally compliant (the exception being the EA currently refusing to agree to an oil well application in the South Downs, and Lancashire County Council turning down two fracking applications only to be overruled by the Government)…

[the DECC has been replaced by BEIS – the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and the Local Authority in this case is North Somerset Council. The Coal Authority is not involved as there is no coalfield within the three Somerset PEDL areas].

The first stage – fulfilling the terms of the initial exploratory stage of its PEDL – will be to drill wells but not frack them. The planning applications will probably clearly state this. Rock cores will be taken out of the wells, and tested for their gas/oil content. The licence-holder (which may change, as licences can be sold on/ transferred at any time) will then enter a five-year “appraisal” period in which more wells could be drilled or existing wells will then be test-fracked. The company can decide whether to move on to appraisal, and then on to development/ fracking.

WHEN

It could be months or years before South Western Energy applies for planning permission, and 10 years before any fracking takes place.

However, if in that time, towns and parishes have surveyed their localities and declared themselves “frack-free zones”, if a groundswell has formed to show future fracking would be unthinkable, if every sector of a community is involved… this can be stopped!

Those who betray the local population by either trying to bury the issue under the carpet, deny the threat of fracking, refuse to discuss it or show their position on it claiming it to be “political” are ironically those who have the most to lose – whether they be elected officials, or often corporate tourism industry types.

If this reaches planning application stage, it will be MUCH HARDER to stop and may only be stopped by physical direct action. This will incur costs to the public pocket, regular disruption including to businesses and transportation and the stretching to breaking point of police resources. So I’d argue those who are reticent to take a stand against fracking now – particularly those in powerful positions – are helping set up their communities and environment up for a fall.

If you’re not convinced fracking is a bad thing I suggest you just google “fracking” and read what you find… including from the most credible news sources. The more you discover the more you are likely to oppose it, from mine and many others’ experience.

MY EDUCATED GUESS

Fracking WILL happen in Somerset if:

- South Western Energy manage to raise the estimated £750,000 to carry out its exploratory work (although there is no public sign of any sizeable assets, they have committed to drilling at least two deep wells in Somerset)

- Landowners within the three licensed areas agree access rights/ lease land for drilling sites

- South Western Energy gets all the necessary permits, consents and planning permissions from the Local Planning Authority, Government regulatory agencies and the Government to drill wells.

- South Western Energy can claim there is gas (or oil) to be exploited from their exploration and then either sell on the licences to a bigger concern or get into fracking themselves (SW Energy have told some people they do not currently have the capability to frack – but there are infrastructure providers and sub-contractors).

- The people of Somerset and beyond don’t stop them getting a foot in the door.

My experience of the anti-fracking movement so far is it cannot be pinned down to a “certain kind” of protester – although surveys have shown middle-aged, female professionals are most likely to be opposed to fracking. I believe there is no right way or wrong way to fight fracking – the widest, most multi-pronged approach is what’s needed – from the WI and parish meeting to anarchist direct actions, from group meetings to autonomous individual actions. All need to be supported, even if it’s not your bag, as it’s all to achieve the same aim.

Fracking is a civil rights issue: it’s a fight to maintain democracy as well as the environment. We shall overcome, we have to! Government may overturn local democratic decisions, or local planners ignore public opinion and massive risks, but when it can be shown there is overwhelmingly no social licence and actions to prevent drills moving in can be justified, it’s only a matter of time and keeping on keeping on before we see this threat off once and for all!

The biggest foe to the anti-fracking cause, aside from the petroleum industry and Government, is inertia and apathy. You might feel like some kind of missionary or evangelist, but wearing anti-fracking T-shirts, distributing leaflets daily, doing what you can to get conversations going must be a constant until we beat this. As is sending emails, letters etc and reading and reading and reading…

I didn’t make it to any of the events (sorry!) but I’ve heard the tour of the film Groundswell Rising, warning people of the impacts the fracking industry has had in America, plus the actions and coming together of Somerset anti-fracking groups are seeing a Groundswell Rising happening in the Somerset anti-fracking zone, with groups now fighting in the Quantocks, Bridgwater and Weston.

I hope I can be of some help with the info amassed below:

GEOLOGICALLY UNITED

I’m in the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, some 50 miles northeast of Somerset, but there is much that unites us with Somerset, besides that we both extend our Rs, convert Ss into Zs and use expressions like “gert lush” and that we are all in Zyder Country…

350 million years ago, whether you were stood on the top of the Mendips or in the Forest of Dean, you would have been either sinking, swimming or wading through a shallow expanse of sea – the Euroamerican Seaway [seen in light grey on this map] – with its coast near the Brecon Beacons and Herefordshire – any further south, and you’d be in deeper waters, the Culm Basin.

The water temperature was warm, tropical – although there was ice and snow in Africa, Australia and South America (then part of the same landmass, Gondwana), we were then situated close to the Equator.

Some 50 million years earlier we, Ireland, Belgium and northern Germany had become joined to North America and Scandinavia.

T he tropical sea was densely populated with crinoids. These creatures, also known as stone or sea lilies, spend their adult lives rooted by a stalk into the sea bed, and wave their mucus-covered five (or more) feather-like arms to trap passing plankton. They are weighed down by hexagonal segments of calcium-carbonate bones or shells.

he tropical sea was densely populated with crinoids. These creatures, also known as stone or sea lilies, spend their adult lives rooted by a stalk into the sea bed, and wave their mucus-covered five (or more) feather-like arms to trap passing plankton. They are weighed down by hexagonal segments of calcium-carbonate bones or shells.

The sediment from the remains of past crinoids developed into a lime-rich mud, and after being buried under more layers of rock and/or soil, was baked into limestone shales.

The sediment from the remains of past crinoids developed into a lime-rich mud, and after being buried under more layers of rock and/or soil, was baked into limestone shales.

The Somerset Good Rock Guide highly recommends Swallow Cliff, 5km north of Weston-Super-Mare for its limestone embedded with volcanic rocks, fossilised crinoids, prehistoric worm paths and lava-petrified coral colonies. (It should be noted though that this is a successive layer of limestone, the Avon Group lies beneath it).

I could also recommend Symonds Yat Rock, or the Avon Gorge in Bristol – from where the Avon Group of Lower Limestone Shales gets its name from.

So what links us now – North Somerset, Gloucestershire and South Wales – is that the petroleum industry, or perhaps just two chancers (the directors of South Western Energy), thinks our shared natural deep-history represented in this, the oldest/ lowest carboniferous rock layer, is ripe for pillaging, and not by conventional means, but by hydraulically fracturing (fracking).

What is peculiar though, is that South Western Energy appears to be the only company which believes Tournasian/ Dinantian, as opposed to later Namurian/ Silesian, carboniferous stone is prospective for gas. In its fairly definitive study of hydrocarbon prospectivity from 2013, the British Geological Survey – commissioned by the Government – says Namurian rocks (from about 40 million years later than the Avon Group and not present in the Mendips or Forest of Dean) are prospects, but does not mention Dinantian (the various layers of carboniferous limestone found in Somerset).

FAULTS IN FRACKING

Fast forward through another 60 million years of history from where we left off… the sea became deeper, resulting in purer dolomite limestone layers (which have been heavily exploited for road-building materials), and then the seabed became a vast area of river delta/ swampland. The first land-based animals and the world’s first forests sprang up, and then were buried by massive mudslides (the submerged forests became peat and finally coal).

The reason for the earth movements was because a land mass, now France and southern Europe, was bashing into Cornwall, Devon and Dorset, squeezed by the collision of North Africa and the massive Gondwana continent to the south of Spain. This crushing resulted in major faults being activated and folding rocks to form the French Massif and Pyrenees, the land being crumpled into mountains and deep valleys – in Somerset’s case, the Mendips rose up and the land south of it (the Somerset Levels) was thrown down, while in the Forest of Dean, the area was raised into a bowl in upland plateau and the Severn Vale and Worcester Graben was thrown down to the east of it. Our area became a mountainous desert, a few hundred miles inland from the eastern coast of the Pangaea supercontinent.

The main risks with fracking are contamination of water and earthquakes (as well as general health impacts). Given that Somerset, South Wales and the Forest of Dean straddle the Variscan Front (as the 2,000km-wide major fault complex which stretches from Ireland to Poland is called). And then there’s the fact this limestone is a “geohazard” – in other words, in the event of a water pollution incident it could be impossible to contain as water spreads rapidly through many pathways through the rock, great distances and unpredictably.

Unlike sandstone, which crumbles as it erodes and soaks up water, limestone is porous and water percolates within it. The dramatic Avon, Cheddar and Wye gorges are testament to that. Water cuts through the rock instead of around it, while – another piece of shared history – the earliest humans to reach Britain inhabited the caves in all three gorges.

Underground there are vast unmapped areas of swallows, caves and sinkholes through which our groundwater runs, at velocities which have been measured at 175 litres per second.

I quote:

It is the Carboniferous Limestone that hosts the best-developed karst landscapes and the longest cave systems in the country. It occurs widely throughout western and northern England and in Wales, and karst features are present on and within the majority of the outcrop (Waltham et al, 1997). Particularly well-developed karst occurs in the Mendip Hills, around the northern crop of the South Wales coalfield (Ford, 1989), in the Derbyshire Peak District and in the Yorkshire Dales and adjacent areas, running up into the northern Pennines. Less well known karst areas include the Forest of Dean, the southern crop of the South Wales coalfield from Glamorgan through the Gower to Pembrokeshire, in North Wales around the Vale of Clwyd, and around the fringes of the Lake District. In all these areas, well-developed karstic drainage systems, sinkholes and extensive cave systems are common.

The major challenges associated with these karst areas are water supply protection, geological conservation and engineering problems. Subsidence associated with sinkhole formation is commonly encountered in remote and rural areas with little impact on property and infrastructure, but damage to houses, tracks and roads is locally a problem. Commonly of greater significance, many of these subsidence hollows are sites for illegal tipping of farm and other refuse or waste, which can cause rapid contamination of the groundwater and local drinking supplies (Fig. 2).

…

Interstratal karst

In parts of South Wales, the Forest of Dean and the Mendip Hills, significant areas of interstratal karst occur. This is where karstic drainage systems have developed in the Carboniferous Limestone below a significant thickness of impermeable rocks such as the Twrch Sandstone Formation or the Cromall Sandstone Formation in the Forest of Dean. There might be little or no surface expression of karst, but extensive caves or karstic groundwater flow systems can occur at depth, such as Ogof Draenen near Abergavenny (Farrant, 2004), and the Wet Sink – Slaughter Risings system near Joyford in the Forest of Dean (Waltham et al., 1997). Areas where interstratal karst is significant have been identified and digitized, making use of geological and topographical maps, groundwater tracing experiment results, cave surveys and expert local knowledge.

There is more general information from the BGS on the geohazard aspects of limestone karst here…

Interestingly, the custodians of Bath Thermae Spa have been assured by the Government that there will be no fracking which could affect the deep underground reservoir which feeds the UNESCO World Heritage hot springs. But no one knows, or is able to prove, just how wide a catchment area feeds into the reservoir. One widely supported theory is that the whole of the Mendips is involved, but one study at least examines the potential of the whole limestone province – from South Wales to the Forest of Dean contributing to the Bath water (see pages 23 to 33).

As for fracking being unsuitable in the UK due to the large number of faults (with the Variscan Front being perhaps the largest complex), let me refer you to Prof David Smythe’s paper to the Government’s Select Committee (2013)…

Ok I have rambled on for far too long now… Just help stop fracking in Somerset and everywhere, everyone who reads this, thanks!

Reblogged this on and commented:

Great article about fracking

LikeLike

Very useful reseach Owen. Thank you for the time, effort and obvious commitment you have to this issue.

BeSt wishes

Kevin Ogilvie-White

LikeLike

Excellent work, such detail! Must have taken ages to pull together. Thank you!

LikeLike

Very informative article. Quite ironic that the picture of Gerwyn shows attractive countryside. It would be interesting to see if he has any photos available to the public of him next to less attractive drill rigs or industrialised once beautiful areas.

LikeLike

Pingback: Owen Adams – SOMERSET… WHAT THE FRACK IS GOING ON? – Frack Free North Somerset